Last February, my thirst for diverse architecture, and the interaction between the developing and developed worlds took me Malmö. There are few other cities in Europe one could visit and learn as much about the state of continent in the 21st century and how it got there. Four issues central to Europe today—regionalism, supranationalism, immigration, and post-industry–are highly visible in Malmö.

- Regionalist Europe:

Malmö is Sweden’s third largest city. It’s the capital and largest city of Skåne, Sweden’s southernmost country. The separatist movement in Sweden most likely familiar to non-Scandinavians is that of the Sami or Lapps in the Arctic North. While people calling for Skåne’s independence from Sweden are a marginal fringe, the region’s identity is clear to see. The Scanian flag (Red with a yellow Nordic cross) rivals the Swedish flag for prominence in public display. Evidence of a Scandinavian dialect continuum, the Scanian dialect spoken in Malmö often sounds closer to Danish than the Swedish spoken in Stockholm. Similar to a phenomenon I’ve heard from Rio de Janeiro to Manchester to Chicago, I noticed announcements on public transport using local dialect rather than a national standard.

- Post-Schengen Europe

Malmö’s proximity to Copenhagen does not mean Skåne is going to join Denmark anytime soon. Rather it’s a case study in European supranationalism, in which two cities function as one metropolitan area with free movement, despite having different national governments. Copenhagen is over twice as big as Malmö, but the ease of train and car communications (about 40 minutes from center to center) means that it is possible to work, live, and play seamlessly between the two cities.

- Immigrant Europe

As I’ve established, Malmö is a Scanian city, a Swedish city, and a European city. But it is also a global city. 41% percent of its citizens were born or have parents born in a different country. What’s fascinating is that no single guest culture predominates. Sweden did not have colonies in the 20th century that contributed to reverse migration from a specific country or set of countries with strong cultural and linguistic ties to the host. Unlike San Antonio, dominated by Mexicans and Central Americans or Bradford dominated by arrivals from the Indian subcontinent, Malmö attracts significant migration from dozens of different countries, with balanced contingents from Iraq, Macedonia, Somalia, Bosnia, and Poland to name just a few. It even drew a disproportionate amount of Chileans and Uruguayans who came to Olof Palme’s Sweden in the 1970s fleeing military dictatorships. For people accustomed to warmer climes and with enough education and income to afford mobility within their new home, Malmö, being the Southernmost and thus warmest point in a frigid Northern country, became a nexus for these political refugees.

- Post-Industrial Europe

De-industrialization hit Malmö pretty hard in the 1970s and 80s. As a city whose main economic role was as a port city rather than a center of government or education, it has had to re-invent itself with the times more than say Stockholm or Uppsala. Today, even with all of the new construction and wealth, there’s still a working class port city air about much of the place. Class tensions–in what many outsiders falsely view as a classless society—are also a contentious issue in 21st century Malmö, though poorly understood compared to regionalism, supra nationalism, and immigration.

These are four thematic European faces of Malmö. Malmö’s different neighborhoods also have many faces, often telling a concurrent story with Europe’s many faces. Interwar apartment blocks on a grid, a historic old city, post-war single-family homes with big gardens, and a massive industrial port are only a few of the urban landscapes in Malmö. As an urbanist, this is a fascinating city to visit. Here’s my account of two neighborhoods that can tell us as much about Europe as they do about Malmö.

- Bo01 in Västra hamnen:

Bo01 is the newest of the new. Pure 21st century, it was built in Västra hamnen (Western Harbor) where factories once lay. It’s a development that emphasises carbon neutrality and other ecological initiatives, and is featured in planning and design manuals all over the world. Cars are third-rate creatures behind bikes and pedestrians. Aesthetically there’s no denying its beauty. Bo01 was no hastily built scheme. 26 different architects have designed buildings on a range of scales, giving a great sense of visual diversity. The highlight of the area is the Turning Torso, a 54 story Santiago Calatrava-designed tower. But as I walked around what is a densely populated neighborhood (names next to all the doorbells tell me that high vacancy rates are clearly not an issue) I began to wonder, where are all the people?

It’s Friday late morning. I assured myself they must be at work. If I were here two hours earlier, or on the weekend, I would see the vibrancy. I went into the MAXI hypermarket across from Bo01 to warm up a bit. I can’t say I was entirely surprised, but the MAXI was comfortably occupied. Not chock full, but far more people inside a big box store than in the entirety of pedestrian Bo01. Bo01 is a mixed-use development. Many of the mid-rise buildings have retail on the ground floor. But all the shops were nearly empty when I walked past. Neither a site of socializing, nor of commerce, they appeared a symptom of a culture that prioritizes boutique over utility.

Bo01 has cute little gelaterias that might fill up on sunny weekends, but for meat, eggs, and toilet paper, a hypermarket trumps any corner shop run by a familiar, trusted local merchant. I’m not suggesting a world where the shopkeeper lives upstairs and spends fifteen minutes chatting with every customer, but at least one where the market provides people places to shop for necessity goods that align with the values of social and economic sustainability that led them to live in the neighborhood in the first place. Now, there’s no way to tell what percentage of this MAXI’s clientele came from Västra hamnen, but what was clear to me is that people vote with their feet. Bo01 may be world class when it comes to low emissions, beauty and quality housing stock, but so much of the sustainable urbanist triumph is undone when I see people shopping in a car-centered big box store, neither socializing with their peers, nor supporting local businesses and brands.

- Rosengård:

I came to Rosengård to see how immigrants have adapted (or failed to adapt) to different kinds of European urban landscapes. Rosengård is a world away from Bo01. Several kilometers southeast of the center, past pre-World War II apartment blocks, Rosengård was built starting in the 60s and 70s as part of the Miljonprogrammet, which sought to build a million new homes for a growing Swedish population. It consists mostly of mono-functional modernist housing blocks built around an expressway and a shopping center. Rosengård has long had an awful reputation as a blighted area in an otherwise peaceful nation. It’s known as a place where one’s way out is to become a football star or hip-hop artist, not a doctor or academic. Zlatan Ibrahimovic, born to newly arrived immigrants from the Balkans, is a son of these parts and local hero.

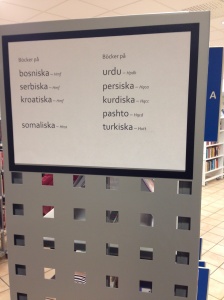

Thus I arrived with bated breath, expecting dangerous at worst, dreary at best. Instead, what I found challenged so much of the urbanist discourse I’ve long heard. The contrast to Bo01 couldn’t have been greater. There were people. Lots of them. Talking to eachother. Mini Zlatans in their #10 jerseys playing five-a-side in a courtyard. Throngs of Iraqi men having coffee in a mall food court. Parents with their children in the library taking Swedish classes or reading in one of the 17 languages for which there are sections. More old men, probably from the former Soviet Union or Yugoslavia, intensely immersed in games of chess. And again, this was during normal working hours on a workday. The same conditions as Västra hamnen, but an entirely different set of results.

One recent touch I liked was the large pictures of residents and food displayed on many of the housing blocks. It’s a sign that humans, everyday people, live here and produce culture worth valuing. It’s the people who inhabit the space that matter, not a dead architect, a corporation, or an intangible ideology. More remarkable about these people and their culture is that I saw no signs of unrest or tension between different immigrant groups, or directed towards Swedes. This is neighborhood where Iraqis and Iranians, Kosovars, Croats, and Bosnians have lived for decades. At a time where immigrant neighborhoods in England and France have seen rioting and terrorist attacks, Rosengård appears rather calm in comparison. I made sure I paused my wanderings for a moment to enjoy the most Swedish of traditions, the fika, or coffee break. But being in Rosengård, it was only appropriate that I stop at a trailer run by a Macedonian on an overpass outside the “City Gross” supermarket, and take my coffee in a Världens Beste Pappa (World’s best dad) mug with burek and baklava rather than cinnamon buns or rye bread. As another antidote to Bo01, entrepreneurs like this witty Macedonian illustrate how small-scale personal businesses can coexist with large-scale development in commercial and physical space.

Malmö is as fascinating an urban laboratory as they come in 21st century Europe. It’s a city that has evidence of planning done right, and planning done wrong, though the two aren’t always clearly discernible. Truly evaluating the success of its neighborhoods, and the influence of welfare state and immigration policies on planning and design requires much more time than my brief perusal. But it’s a great place to observe so many processes in contemporary Europe because of how different geographic scales collide with different building scales. Malmö gives us clues about a question I will continue to investigate: To what extent can architecture and planning provide immigrants in 21st century Europe their own expression in a design tradition dominated by that of host nations? As Malmö, Skåne, Sweden, and Europe become more and more pluralistic, architecture must reflect this. It’s counterproductive for either one style to emerge above all others, or for certain styles to be abolished all together. Malmö illustrates that bland housing blocks can sometimes be very socially active, and that pedestrian eco-neighborhoods can sometimes a bit boring and socially contradictory to their supposed values. But the reality is more fluid, and a case in point that building types do not have universal social outcomes. A snapshot from 2014 is not static, but reflects an entirely different reality from either 1973 or 2050.